Native Australian Animals Trust

A hundred million years of isolation has made Australia's fauna unique. We harbour some of the most ancient lineages on earth: marsupials, monotremes, reptiles, amphibians, and arthropods. Australia's animals hold a treasure trove of secrets from which we can all benefit, and they require careful custodianship and thoughtful approaches towards their conservation.

The Trust

The Native Australian Animal Trust is a way for people passionate about Australia’s wildlife and their environments to connect with and support the University of Melbourne’s research, teaching and engagement activities. Philanthropic gifts to the Trust are already funding some of our students and researchers who are working on a range of important environmental and ecological projects.

If you would like to give to the Native Australian Animals Trust, you can do so via the button below or learn more about giving.

Our Patron

The Patron of the Native Australian Animals Trust is multi-award-winning Australian author, Tim Winton. The natural world plays a central role in Tim's work as a novelist and essayist, and he has long been a passionate advocate for the Australian environment. His involvement with the Native Australian Animals Trust reflects that passion.

The encounter between ourselves and the land is a live concern. Elsewhere this story is largely done and dusted, with nature in stumbling retreat, but here our life in nature remains an open question and how we answer it will define not just our culture and politics but our very survival.

The Big Science Pitch

With just three minutes to sell their idea, the competitors need to convince the judges, the public, and author Tim Winton that their project is most worthy of receiving funding from the Native Australian Animals Trust.

Philanthropy allows researchers and students from across the School of BioSciences to focus on what they're best at - protecting and promoting Australian wildlife, ecosystems and environments. If you would like to give to the Native Australian Animals Trust, you can do so via the button below, or find out more about giving to fund research such as this.

Fundamental biology and ecology of Australian animals

From the behaviour of insects to the genetic underpinnings of foetal development and assembling the genome of the Thylacine, we are leaders in fundamental biological research. This research often yields new applications with possible benefits to human health, such as work on the genomics of marsupial development, which led to the identification of novel milk proteins and anti-microbial peptides.

Uncovering hidden biodiversity

Our researchers traversed the remote rivers of the Kimberley region in Australia’s north over a period of two years, discovering 20 new freshwater fish species - the greatest single addition to Australia’s freshwater fish fauna since the first such species was described more than 187 years ago. Now that we know these species exist, we can mount arguments for their protection – and go searching for others.

Evolutionary approaches to rescuing populations

Species don’t go extinct overnight. Firstly, there’s a period of decline, and this is our chance to save them. Our researchers are introducing particular genes to populations that need our help to survive. We’re already teaching quolls to be ‘toad-smart’, breeding coral that can survive in warmer waters, and expanding the gene pool of the mountain pygmy possums based at Victoria’s Mount Buller.

Saving species in rapidly changing landscapes

In the face of human expansion, how do we identify which regions and habitats should be preserved to protect different species? Our researchers are world leaders in solving precisely this kind of problem. We identified which habitats around Perth in Western Australia can best protect nearly 200 threatened species, resulting in a regional plan that sets aside 170,000 hectares for new natural reserves, optimally arrayed to protect biodiversity.

Linking with Indigenous communities for conservation

Indigenous protected areas place land management firmly into the hands of the Indigenous owners, creating stronger links to country. Our researchers have a proven track record of finding out what land managers want and helping them work out how best to get there. We’re collaborating with communities to integrate Indigenous knowledge with scientific methods, facilitating social, economic and environmental benefits for Indigenous people, and building their capacity for natural resource planning.

Dealing with disease

Almost everything we know about disease evolution comes from biological research. Our researchers discovered that female mosquitos infected with the Wolbachia bacteria don't pass on the Dengue virus and, when they mate with non-infected males, produce no offspring. This biological control program is helping to suppress mosquito populations in several countries by effectively immunising them (and us) against Dengue. We've also examined the evolution and physiology of malaria, and developed new tools to reduce drug resistance, which may help us to combat malaria permanently.

Turning back the tide of invasive species

Foxes, cats, invasive plants, invasive diseases and invasive toads have had a huge impact on Australia’s biodiversity. Our researchers have developed innovative strategies for dealing with these species, from preventing their arrival to containing their spread and mitigating their impact. We are now at the forefront of new genetic techniques that may revolutionise our ability to control and eradicate invasive species, and our work on evolution in invasive species is even being applied to an invader of personal concern to most people: cancer cells.

Philanthropic support received by the Native Australian Animal Trust goes towards our students and researchers, with the first awards made in 2018 to the recipients profiled here. If you would like to give to the Native Australian Animals Trust, you can do so via the button below, or find out more about giving. Your support will help to make possible more projects such as these.

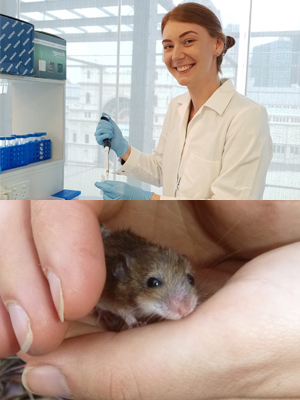

Emily Roycroft: Cryptic species in the delicate mouse

Undefined species are problematic for conservation assessment, as species cannot be protected if they are not identified and classified. Preliminary data from across the range of the broadly distributed native Australian delicate mouse (Pseudomys delicatulus) has indicated the presence of three separate species. Using a combined genomic and morphological approach, this project aims to assess species boundaries and test for hybrids across the delicate mouse range. Characterising the pattern of genetic divergence in the delicate mouse will help inform conservation action, and add to our understanding of how past environmental change has driven the diversification of native species in Australia.

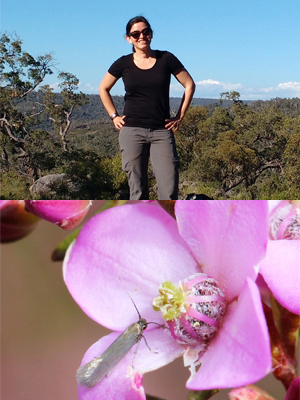

Liz Milla: Evolution and ecology of Australian Heliozelidae moths

Heliozelidae are a family of very small, day-flying moths, with many previously unknown species recently discovered in Australia. One group of Australian Heliozelidae are the exclusive pollinators of some Boronia plants. The female moths pollinate the Boronia flowers, and the caterpillars feed on some of the developing seeds. This is known as an obligate pollination mutualism, a rare and very specialised type of plant-insect relationship. With support from the Michael Mavrogordato Award, I will be able to classify these small moths using their DNA sequences, helping us understand how many different species are involved in this pollination mutualism, and how it may have evolved.

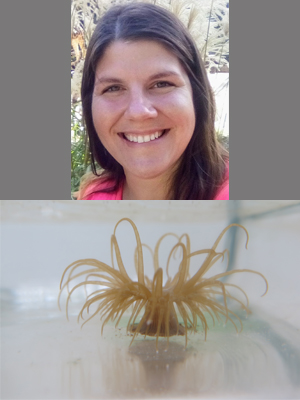

Francesco Ricci: Physicochemical micro-niches in coral skeletons

Many microorganisms live in association with reef corals, playing important roles for their hosts and within the reef ecosystem. So far, little attention has been given to microbes living inside the skeleton and its micro-niches. Hence, my PhD project in the context of the skeleton will describe the microbial communities and determine its physicochemical properties in Porites and Goniastrea species, allowing to comprehend the relations between microbes and physicochemical gradients.

Christopher Jolly: Are species reintroductions inherently dangerous?

Most reintroductions of native animals to the wild fail. There are a lot of context-specific reasons why they fail – but could it be that simply the movement of animals into an area they’re unfamiliar with is just inherently dangerous? In this study, we plan to test this question at Arid Recovery by moving cat-smart endangered burrowing bettongs and cat-smart, invasive European rabbits to a new area where feral cats are present. We will compare the movement and survival of moved animals to those of bettongs and rabbits that already living in this cat-invaded landscape.

Ashley Dungan: Introducing climate resilience in corals

In the past two years, 50% of the living coral on the Great Barrier Reef has died. The cause is thermal stress, which results in a phenomenon called coral bleaching. My project investigates the production of beneficial chemicals, called antioxidants, by bacteria that live with corals to protect them from thermal stress. Corals are colonised by billions of bacteria that have a profound influence on their health. I hypothesize that we can adjust the coral’s bacterial communities by increasing the number of antioxidant-producing bacteria and protect corals from bleaching. The outcome of this project will be the development of a probiotic derived from naturally existing bacteria that increases climate resilience in corals.

Edward Tsyrlin: DNA barcoding of sand flies (Ceratopogonidae, Diptera) in Victoria

Despite being an import indicator of River Health around the world, species of sand flies (Ceratopogonidae) are still poorly known in Victoria. One of the main aims of my PhD research is to conduct taxonomic studies to describe and spate common species of this group within the Greater Melbourne area. I will be using DNA barcoding and morphological features to separate these species and to associate larvae and adults. These findings provide a basis for detecting sand fly species from water and sediment using environmental DNA, and pave the way for efficient biomonitoring of our freshwater ecosystems.